|

Today's Opinions, Tomorrow's Reality

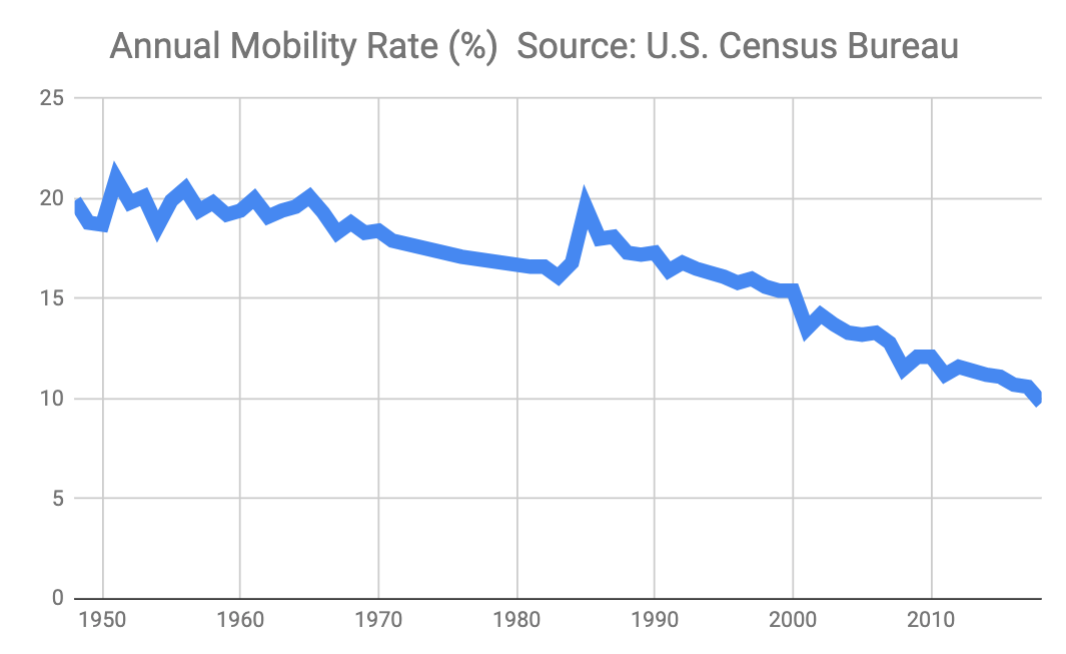

Losing Their Gumption By David G. Young Washington, DC, July 2, 2019 -- Many Americans have lost the will to move to improve their lives. That makes them unworthy of their own great country. The image of a drowned father and daughter on the Rio Grande has exacerbated America's divide over immigration. Depending on which side you are on, migrant deaths are either caused by The Trump administration's brutal border policy, or lax border controls that entice migrants to commit illegal and irresponsible acts. Whatever the truth, there is no denying that Central American migrants are willing to go to extreme lengths and make huge sacrifices to seek of a better life in the United States. Clearly, Americans cannot relate to this behavior. Migrating for the sake of a better life is at an all time low in the United States. Since 1948, the first year the Census Bureau began tracking the statistic, the mobility rate of Americans has declined from 20 percent per year in the early 1950s to 9.8 percent last year.1 This mobility statistic tracks the number of people who move from one address to another within the United States.

This is important because much of the nativist sentiment that drives America's hard-line border policy comes from the Trump Administration's political base of disaffected industrial workers. Instead of agitating for government action to return to industrial greatness, why don't they simply migrate to areas of greater opportunity? This is exactly what many of their ancestors did in migrating from Europe or American farms in the late 19th and early 20th century. It's the same thing that Central Americans are doing now. Many theories have been offered to explain America's falling mobility rate, much of it related to economic change. During the industrial era, large new factory openings might require thousands of assembly line workers. Workers recruited family and friends to join them en masse in new communities. But automation has cut the density of people needed to build products, requiring less migration. What's more, economist Timothy Taylor notes that cities are actually less specialized than they used to be.2 Steel workers once flocked to Pittsburgh or Gary, while automotive workers moved to Detroit. Today's service industries are less concentrated--cell phone shops, call centers and warehouses exist in cities across America. There is no point in moving to another city to get a job when that same job is available close to home. But often the same job in a different city pays much more, espeically in America's booming coastal cities. San Francisco and Washington DC now have median household incomes over $100,000 per year--nearly double the income of poorer cities like Tampa and Detroit.3 And while the disparity within these rich cities has opened a gulf between knowledge workers and the rest, governments have responded by boosting minimum wages to $14-$15 in the case of the leading cities mentioned while they lag at. $6-$9 in the trailing cities. Without question, people working the same jobs in these cities make more money. The drawback is higher living costs--especially high housing costs take a big bite out of these wages. Low income workers must live in group houses to make ends meet--that's what the cities' students and international immigrants do. And it is also exactly what many people did in America's earlier waves of migration. Not everybody is willing to do that. Most Americans want to live in a big house close to family and friends. A study by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York found that the average person today would forgo 30 percent of his or her income in order to remain close to home.4 It's a good bet, though, that people 50 years ago felt the same way. What has changed is that Americans today have much, much higher incomes. Disposable income per capita adjusted for inflation has quadrupled since 1960.5 Back then, moving vs. not moving could be the difference between having food on the table and going hungry. The number one reason Americans' won't move today is because they can get by without doing so. A 2016 Bloomberg study found that Social Security disability claims are highly concentrated in economically depressed areas like Appalachia and the Great Lakes regions, growing from serving 2.5 percent of Americans nationally in 1990 to 5.2 percent in 2015.6 The highest growth rate in claims was for neuroskeletal and connective tissue disorders--a category that includes easy to diagnose but hard to disprove chronic back pain. Why move for a job when Uncle Sam will pay you to live near family and friends in your downtrodden hometown? Clearly not all nativist Americans are poor homebodies living on the dole. But statistics do show that most Americans have lost that very gumption that played a huge part in making America great. The fact that many can't even respect this admirable quality in people crossing our southern border is perhaps the saddest development of all. Notes: 1. US Census Bureau, Annual Geographical Mobility Rates, By Type of Movement: 1948-2018, as Posted July 2, 2019 2. Planet Money, Americans Are Moving Less Than They Used To. Don't Blame The Recession, December 11, 2012 3. US Census Bureau, iHousehold Income: 2017, September 2018 4. City Lab, Why Some Americans Won't Move, Even for a Higher Salary, May 30, 2019 5. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Real Disposable Personal Income, historical figures as posted June 17, 2018 6. Bloomberg.com, Mapping the Growth of Disability Claims in America, December 16, 2016 |